This Week’s Lesson – Don’t Eat That Bird!

The Last Bite

The Problems of Translation

In our last lesson – Don’t Eat That Bird! Part 2 – we touched upon the translation uncertainty of the “unclean bird” names found in Leviticus 11:13-19. We now look farther into that uncertainty, and contemplate the ramifications of what we find.

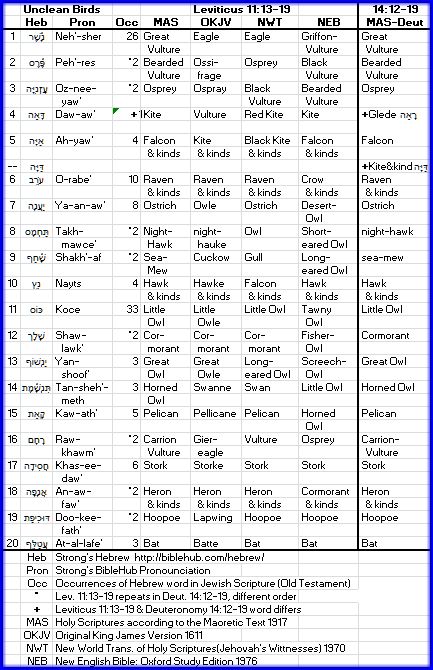

The Unclean Birds chart below lists the Hebrew names and pronunciations, the number of times each name occurs anywhere in the Jewish scriptures, English names chosen by the translators of four English versions, and the names from the similar – but not identical – list in Deuteronomy 14:12-18. The twenty-one names listed in Deuteronomy are in a different sequence from that of Leviticus; I put them into the Leviticus sequence to simplify comparison.

If we compare the versions shown above, we find such “equivalences” as:

(7) Ya-an-aw`: ostrich, owl, desert owl

(9) Shakh`-af: sea-mew, cuckoo, gull, long-eared owl

(14) Tan-sheh`-meth: horned owl, swan, little owl

(15) Kaw-ath`: pelican, horned owl

(16) Raw-khawm`: carrion-vulture, gier-eagle, vulture, osprey

It should be obvious that no sane human actually confused an ostrich for an owl, or a horned owl for a swan. The problem originates elsewhere.

The chart above shows forty possible English translations for the twenty Hebrew names of our unclean birds, and that’s from only four English translations. [I eliminated obvious equivalences as: Bearded Vulture and Ossifrage, Osprey and Ospray, hawk and hauke.] We also find the same English name in different locations in the four Leviticus lists. For example, birds 2 and 3 seem to have interchangeable translations, even though the Hebrew words are quite different. The twenty Hebrew names in Leviticus don’t shift positions, but their English translations certainly do. If we examined the dozens of bible translations, we would find even more translation variances for these twenty Hebrew words.

Little Owl (Trebol-a 3-21-10)

Ostrich, Addo Nat. Elephant Park, Saudi Arabia (Kore 11-21-13)

Here’s the cause of the problem. The occurrence column shows how many times each word occurs in the bible. For example, Daw-aw` דָּאָה (note the small diacritical dot inside the last character) “kite” occurs only once (replaced in the Deuteronomy list by רָאָה (no dot) – raw-aw` “glede” and/or דַּיָּה – dah-yaw` “kite”). [Ancient Hebrew had no written vowels. As centuries passed and original pronunciation forgotten, diacritical marks were added to the letters, and comments on pronunciation made in the margins. Needless to say, despite extreme efforts to maintain accuracy, errors and changes occurred.] These three words look and sound similar and apparently all refer to the very same bird, so they may constitute ancient biblical typographical errors. The most common of the twenty names, Koce “Little Owl,” has only thirty-three occurrences; compared to the most common words which occur thousands of times, that’s not many.

In short, it’s very difficult to know what rarely used words really mean, especially when their usage is always in the same context.

Red Kite – Gredos Mtns, Avilo, Spain (Arturo de Frias Marques 12-8-12)

Black Kite – Iwata, Shizuoka, Japan (Nubobo 1-11-14)

New Unclean Birds

If you guessed that “glede” has something to do with “glide,” you are correct. Oxford English Dictionary (OED) traces it to Old English “gleda;” usage citations range from 725 CE to 1884 CE. The name, usually applied to the Red Kite Milvus regalis [now M. milvus], is “also locally applied to other birds of prey, as the buzzard, osprey and peregrine falcon.” Unfortunately for British biblical translators, Red Kite, common in Western Europe, does not occur at all in Palestine. However, Black Kite M. migrans migrates through Palestine, with a small wintering population in northern Israel. Closely related, these two species occasionally interbreed, and were likely difficult to differentiate in olden days. With “glede,” translators doubled the confusion by choosing a name applied to at least five species as translation for a Hebrew name of uncertain meaning.

Little – Ekaterina Chernetsova, 5-15-14, St. Petersburg, Russia

Black-headed – Barak Baram, Israel, Feb. 2010

White-eyed – Alexander Vasenin, Red Sea, 5-3-13

The OED gives citations from 1430-1890 CE for “Sea-mew,” known to us as Larus canus, the Mew or Common Gull. “Mew” is the Old English name for the bird, referring to the plaintive cry of most gull species, and this one in particular. Eight gull species regularly appear in Palestine: Slender-billed, Black-headed, Little, Mediterranean, Pallas’s (aka Great Black-headed), Audouin’s, Mew, Armenian (previously sub-species of Yellow-legged) and Lesser Black-backed. Two additional species – Sooty and White-eyed Gulls – are Red Sea breeders, wandering as far north as Eilat. The smallest species, Little (L 9-11″, WS 24-27″) is about 40% the size of the largest, Pallas’s (L 23-26″ WS 57-64″). Gulls are found on the coast as well as inland throughout the Jordan Rift Valley. The unclean bird list didn’t say “the gull after his kind,” so either they thought they were all one “kind”, or שָׁ֫חַף – shakh`-af was not a gull at all.

(Wiki Commons)

Ostriches Struthio camelus no longer occur outside of Africa; the Arabian Ostrich S.c.syriacus race was hunted into extinction by 1966. Although they were popular meals for Romans, the Israelites considered them both unclean and “heartless” (Lamentations 4:3), the latter because they leave their eggs unattended as their thick shells are sufficient protection from predators. Ostriches eat mostly grasses, seeds, leaves and succulent plants, plus some insects and lizards, so I can’t see why they would be unclean. It must have been hard for the Israelites to pass up eating a ten-foot-high, two hundred and fifty pound bird, large enough to feed a family for many days.

Osprey at Malibu Lagoon – another possible Gier-eagle (Randy Ehler 9-26-16)

There are yet more variations. Gier-eagle, by most accounts, refers to the Egyptian Vulture Neophron percnopterus, an important carrion-eater ranging from Cape Verde Islands eastward to Bangladesh. The cuckow, or cuckoo, is the Common Cuckoo, Cuculus canorus, [link includes call] beloved bird of Swiss clock-makers, and widespread across Europe and around the Mediterranean.

Clock Cuckoo who looks more like an overstuffed canary (Popscreen)

The Night-hawk is almost surely the European Nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus, also widespread across Europe and the Mediterranean, dining nightly on any flying insect. Other possibilities are Egyptian Nightjar and now very scarce Nubian Nightjar, both of which barely reach Palestine. The swanne seems out-of place: none breed in Palestine and the current population of wintering Mute Swans Cygnus olor in the area is exceedingly small. Perhaps the few mollusks they eat made them unclean, but I think it a misinterpretation; תִּנְשָׁ֫מֶת – tan-sheh’-meth is likely an owl, perhaps the easily confused (I’m joking) Horned or Little Owl some translators suggest.

Nubian Nightjar תחמס נובי – Neot Hakikar, Israel (Yoav Perlman Mar’09)

Unless you like fish – and the Israelites and later Jews ate fish – you probably wouldn’t want to eat a pelican קָאָת – kaw-ath’ as that’s all they eat. Mostly skin, feather and bone – unappetizing, certainly, but unclean? I don’t see why. Great White Pelican Pelecanus onocrotalus (not our American White Pelican Pelecanus erythrorhynchos) migrates through Palestine and a small population winters in northern Israel. The larger Dalmatian Pelican Pelecanus crispus once numbered into the millions, but is now rare and still dwindling. They breed around the Black and Caspian Seas, wander widely post-breeding, and maintain a wintering population in Lebanon and northern Israel. They were likely very common in Palestine in biblical times.

Dalmatian Pelican (Marcel Burkhard)

Great White Pelican – Liesbeek River, Cape Town, SA (Andrew Massyn)

Similarly, the cormorant שָׁלָך – shaw-lawk’ is piscivorous; if you are what you eat, a cormorant must taste like a fish. They are, however, quite messy in their nesting habits, as are pelicans, and anyone might be reluctant to eat a bird that seems to wallow in its own excrement. In Palestine, they come in three flavors: Great Cormorant Phalacrocorax carbo, European Shag P. aristotelis, and Pygmy Cormorant Microcarbo pygmeus. All three winter in the vicinity of Palestine; the Pygmy is resident year-round.

Great Cormorant – Hyogo, Japan (Miya 10-28-05)

Pygmy Cormorant – Hortobagy, Hungary (Martin Mecnarowski 6-18-10)

European Shag – Brownsea Island, UK (Ian Kirk 2-23-13)

I don’t have data to support this conjecture, but it seems that among carnivorous mammals (including humans) it’s a general rule that – except for eating fish – they prefer eating herbivores, but will eat omnivores when necessary. Carnivores sometimes kill carnivores to eliminate competition, but they don’t seem to eat them. Other than dogs (and fish), I can’t think of any carnivore that humans willingly eat. It doesn’t take much imagination to see that this preference would easily extend to the eating of birds.

Final Comment on Bible Bird Study Lessons I – X

The genesis of these essays began about fifteen years ago, when I wrote a series of six installments of “Birds in the Bible” for the newsletter of the church I attended. In that situation, all the readers were Christians and none were birders. I suspect the current situation is almost the opposite: very many birders and very few practicing Christians. The content of the old pieces constitute about 5% of the new.

At the beginning of lesson one, I wrote “Whatever one may think of the bible, it was unarguably written long ago by humans not significantly different than us, who wrote about what they knew and what they imagined, just as we do today.” Everything that followed is my support for that statement. Humans wrote the books for human reasons. These ten “lessons” were a phenomenological exercise in which we “bracketed” – suspended judgment about a phenomenon – in this case the bible – in order to analyze the experience. The bible is a phenomenon – it inarguable exists – but whether any of what it says is true is another matter, not under our investigation here. By incorporating what humans have learned about birds over the intervening millennia since the bible books were written, we found that sometimes the biblical writers sufficiently understood a bird’s behavior to reasonably incorporate it into their narrative. But sometimes not, which inevitably led us into textual analysis, where we found that in some cases it is as yet impossible to determine what the original words – as they have come down to us – actually meant. At the very least, we learned something about the birds that were out and about in those days in that region, and about those who observed them.

Bible Factoid #10 – Rare Words in the Bible

The Jewish scriptures have 8,674 different Hebrew root words (ignoring the addition of letters to change the case – “crow,” “crows,” “the crows,” “all the crows”). Four hundred (1) (4.6%) of these words are used only once. There are undoubtedly more words that occur only twice, and even more that occur only three times, far too few for certainty of meaning. In the Greek New Testament, there are 5,624 different words, of which 1,934 are used only once, or a whopping 34.4%. [On the other hand, the twenty-seven most common Greek NT root words constitute more than 50% of the 138,000 total GNT words.] The New Testament (NT) was written in Koine Greek, different from classical Greek. Some Koine words do not occur at all in classical Greek texts. How then, can we be certain of the intended meaning of such rare words? How can we feel confident that English translations of these ancient books are accurate, when the translators who actually know and read these ancient languages are literally using an educated guess as to the meaning of many of the words?

The short answer is: we can’t. I think that translations are as good as translators can make them. Although there are instances of intentional textual changes – Mark 16:9-20 is widely held to be a later addition – most variations are accidents. The number of unintended copying errors made during the early centuries, when scribes and monks copied scriptures by candlelight, are still beyond count. A single-letter copying error creates a new “version” of the bible. Bart Ehrman, in Misquoting Jesus, estimates there are between 200,000 and 400,000 such “versions” of the New Testament.

The number of translation differences we see in the list of twenty unclean birds is a peek through the door, for both birder and biblical neophyte, at the difficulties encountered when one attempts to know what the bible really says. We’ll take one more peek, this time with a famous and controversial phrase from what is probably the best-known passage in the New Testament, the Lord’s Prayer (Matthew 6:9-12 & Luke 11:2-4), found in Matthew 6:11 and Luke 11:3.

The word ἐπιούσιον – epiousion, translated as “daily” as in “daily bread,” occurs only twice in the entire NT, both times in the context of the “Lord’s Prayer,” and occurs nowhere else in the entire body of Greek writing prior to the NT. This single context makes accurate translation impossible, just as with the names of the unclean birds. New English Bible says “daily bread,” but footnotes it with “or our bread for the morrow.” Oxford Companion to the Bible has “the bread we need for tomorrow,” adding as interpretation that we should concern ourselves with one day’s ration of food and leave the rest to God. An interpretation I learned in church was, “give us today the same spiritual food we will receive in our (eternal) future,” or shorter, “feed today our eternal souls.” This site gives five interpretations. Methodist minister Adam Clarke (1769-1832) had an interesting explanation: Travelers in the east ate the preceding evening’s leftovers for breakfast. The source of the next evening meal was unknown, so they must rely on God’s providence.

But the word ἐπιούσιον – epiousion, is just too rare for certainty, and the intended meaning is probably lost forever. This critically important and best known passage in all of Christian literature is afflicted with the same ambiguity we found in our list of unclean birds, caused by the uncertainty in meaning of these ancient, rare words. This provides no comfort for those who demand biblical inerrancy, who cannot abide uncertainty. But for those who can tolerate uncertainty – and really, who can be 100% certain we will even live into the next minute – and whose faith has flexibility, it’s merely a minor bump in the road.

Final Note on the Bible Factoids

The factoids started as an afterthought, and weren’t called factoids until #4 was written, at which point I went back and renamed them. After the lesson on the doves and flood was posted, I recalled that few people know of the much older flood narration in the Epic of Gilgamesh, and thought it deserved a mention. The other factoids were topics I had found surprising and interesting during my own study of the bible, many years ago. I was still curious about several of the topics, and writing the factoids gave me the impetus to learn more, especially the evolution of Jesus’s name, the two bar-Abbas’, the Reed Sea, On “On,” and “daily” bread. Of “Of” was a special case – it’s something which had bothered me for decades; now I feel better. I had several other factoids written, but ran out of birds to run them with. I consider such factoids to be anomalies, peculiar items that don’t fit into the ordinary conversation on biblical matters.

Thomans Kuhn’s book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, was itself a scientific revolution, critically important in the history of the last century. By creating the concept of “paradigm shifts,” it thereby became its own paradigm shift. “Normal science” functions to fill gaps in our current model (viewpoints, theories, worldview) of reality. Inevitably, anomalies – events unexplainable within the current model – begin to appear. Such anomalies proliferate, forcing many to acknowledge the model as insufficient. Eventually a new model appears which explains the anomalies, and the process begins anew. I see religion in general and Biblical (and Koranic) studies in particular as models of reality currently shot through with anomalies. The revolution in biblical textual analysis began in the 19th century, yet is nowhere near finished. I can’t see that a similar process has even begun on the Koran. As long as the majority of people continue to view these texts as untouchable, sacrosanct, beyond criticism, we will remain trapped within these ancient models, which even now creak and crumble. These texts are culturally foundational texts, created by the amazing minds of humans; to treat them as deity-created diminishes both deity and human alike.

Part I – What About That Dove? & The Flood of the Gilgamesh

Part II – Sandgrouse or Quail? & YHVH [יְהוָ֖ה] [Yahweh]

Part III – Junglefowl in Judea! & New Testament Koine Greek

Part IV – Birds that Sow, Reap and Store & Whence Jesus (Ἰησοῦς)

Part V – The Friendly Raven & The Bar-Abbas Mystery

Part VI – The Humble Hoopoe & Catching “Forty” Winks

Part VII – The Wise Hoopoe & On “On”

Part VIII –Don’t Eat That Bird! Part 1 & Of “Of”

Part IX – Don’t Eat that Bird! Part 2 & Seeing “Red”

[Chuck Almdale]

Additional Sources:

1. Birds of Europe. Mullarney, K., Svensson, L., Zetterström, D., Grant, P.J. (1999) Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J.

2. Dictionary of American Bird Names. Choate, Ernest A. (1985) Harvard Common Press, Boston.

3. Handbook of Birds of the World (HBW), Vol. 1. del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Sargatal, J. eds. (1992) Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Ostrich – Pg 83.

4. Handbook of Birds of the World (HBW), Vol. 2. del Hoyo, J., Elliott, A. & Sargatal, J. eds. (1994) Lynx Edicions, Barcelona. Vultures – Pgs 125-129.

5. Holy Scriptures: According to the Masoretic Text. (1955) The Jewish Publication Society of America. Philadelphia. [A 1917 translation]

6. Misquoting Jesus. Ehrman, Bart D. (2005) Harper Collins, San Francisco, Ca. Pg 89.

7. New English Bible with the Apocrypha, The: Oxford Study Edition. Sandmel, Samuel, Suggs, M. Jack, Tkacik, Arnold J.; eds. (1976) Oxford University Press, New York.

8. New World Translation of the Holy Scriptures. (1961) Watchtower Bible and Tract Society of New York, Inc. New York.

9. Oxford Companion to the Bible. Metzger, Bruce M. & Coogan, Michael D. (1993) Oxford University Press, New York. Pg 465.

10. Oxford English Dictionary. (1971) Oxford University Press, New York.

Sources With Links:

BibleHub.com An invaluable tool. Almost a “one-stop-shopping” research site for the bible.

BibleStudyTools.com A very useful site.

(1) Hapex Legomenon – Wikipedia – Section “Significance,” paragraph six. Words that occur only once within a particular contex.

You must be logged in to post a comment.