[By Chuck Almdale]

[NOTE: If maps, pictures and legends don’t display properly in your email, go to the blog. The interactive Google map within this posting works on the blogsite, if not in your email. There is a link at the bottom to the entire Mongol Empire & Rus’ series.]

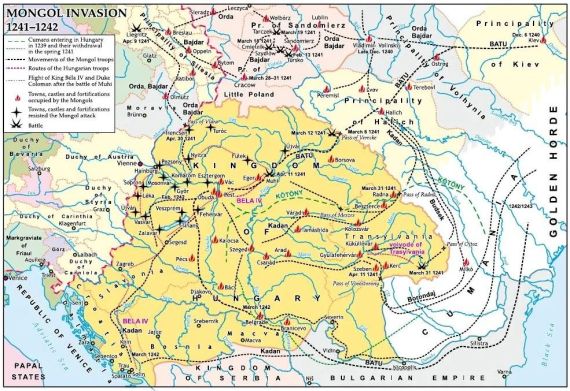

1241 Central Europe invasion, movement, and exit routes; Josef Szabo.

Source: Academia – Mongol Invasion of 1241

The Racibórz Crossing

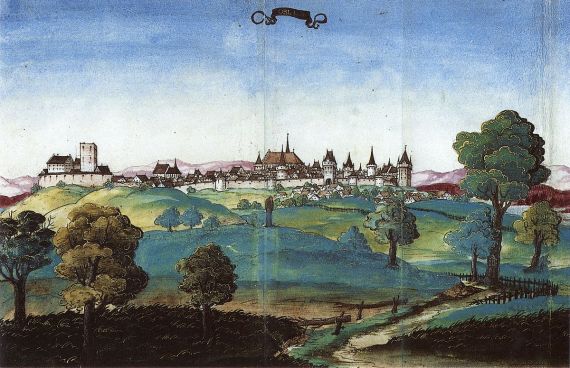

The next town mentioned is Racibórz 75 miles west of Kraków, one of the historic capitals of Upper Silesia and from 1172 to 1521 the residence of the Dukes of Racibórz. It is very strategically located on the Oder River near where it flows out of Moravia through the wide valley known as the Moravian Gate, then past Opole and Wrocław and north to the Baltic Sea. According to this site, the Mongols arrived at Racibórz on 20 March [thus before Kraków was sacked] and encountered an army of Silesia under the leadership of the Duke of Racibórz and Opole, Mieszko II the Fat. After these units of the Mongol army reached the Oder River near Racibórz and were trying to cross, the Duke decided to attack them and it would seem they successfully beat them back, at least for a while.

Racibórz city plan of the year 1567, by Olos88.

Source: Wikipedia – Racibórz

The major rivers in Poland generally freeze up in January, several months later than in Rus’ as the climate in Poland is milder due to their proximity to the Baltic Sea. As of 2023 the Oder river is iced over for only 40 days a year. The modern custom is to break up the ice in January and February with ships; moving it downstream at this time reduces the probability of springtime floods that result from allowing the ice to break up naturally. In late March 1241 the ice on the upper Oder had probably already melted or was too thin and slushy to safely cross. The Mongols would have to use their personal floatation devices to cross the river or build rafts: the first would be a painfully cold process for man and horse alike, while the second would be safer and more comfortable, but time-consuming. After this battle Duke Mieszko’s army rode off towards Legnica, and joined the army assembling there under Duke Henry II the Pious of Silesia, which led to the Battle of Legnica, where we will soon arrive. Despite their ravaging Poland, time moved on after the Mongols left. Duke Mieszko II later founded a Dominican monastery in Racibórz where he was buried in 1246, at the young age of 26. Some say it was because he was far too fat for his own good.

Ice jam on the Oder River at Frankfurt/Oder on 24 February 2012 (photo by Halka Beberstedt). Source: MDPI – Oder Ice Jam Flood

Skirmish at Opole

The Mongols managed to cross the Oder river despite Duke Mieszko’s attack. Once across, they decided not to besiege Racibórz, which apparently was well-fortified. It’s entirely possible they could not get their catapults and other siege equipment across the dangerous river. Instead they more or less followed the Duke down the Oder River to the city Opole, 40 miles to the north.

Oldest known view of Opole seen from southeast, circa 1535. From Angelika Marsch Oppeln, Falkenberg, Gross Strehlitz. Historische Ansichten aus vier Jahrhunderten. Bergstadtverlag Wilhelm Gottlieb Korn, Würzburg 1995; original picture is in Würzburg University Library (Germany).

Source: Wikipedia – Opole

A century after the Mongols came through this region, Opole, the entire Duchy of Opole and most of Silesia fell under the control of the Kingdom of Bohemia, centered south of the Carpathians in what is now the western half of Czechia, and itself then part of the Holy Roman Empire. But in 1241 CE Opole was the primary capital of Upper Silesia. When they reached Opole they found the knights of Racibórz had joined with the forces of Władysław I [Vladislaus] Duke of Opole; forces from Lesser Poland (the provinces of Kraków and Sandomierz) had also arrived. A short battle ensued between these united armies of the Polish Dukes and the Mongols. Despite the various cities they represented, the Poles were still outnumbered by the Mongols, and they retreated towards Wrocław, the Mongols following, and then westward to Legnica where they joined the massed forces of Henry II the Pious, Duke of Silesia and High Duke of Poland. Again the Mongols followed and they reunited with Orda’s army at Wrocław. The Mongol right flank in Poland was now back at maximum strength.

Portion of Opole medieval defensive wall. Photo: SuperGlob.

Source: Wikipedia – Opole

Duke Henry the Pious Awaits

It was early April 1241 and Duke Henry II the Pious of Silesia awaited the Mongols’ arrival. He had heard what happened to other cities in Poland. He knew the ‘Tartar’ army had badly beaten Boleslav V, his cousin, and pillaged and burned Boleslav’s city Kraków. As he rode through his city of Legnica, a stone fell from the roof of St. Mary’s Church and narrowly missed killing him. Those watching saw it as an evil omen.

Henry anxiously awaited his brother-in-law, King Wenceslas I of Bohemia, to arrive with 50,000 men, and wondered if he should have stayed behind his city walls until they arrived. But he greatly feared the possibility that additional Tartar reinforcements might be on their way. [One might say they were, as the two Mongol armies reunited at Wrocław. Beyond that, there were no more coming.] Henry cast his lot for immediate battle, and on April 9th 1241, he led an army of 30,000 Polish knights, Teutonic Knights, French Knights Templar and a levy of foot soldiers, including German gold miners from the appropriately named town of Goldberg. They headed towards where they hoped to meet the Bohemian army. They also expected to encounter up to two full tümens — about 20,000 battle-hardened Mongol cavalry — somewhere on the Wahlstatt plain, commanded by Orda and Baidar, in what would come to be known as the Battle of Legnica [Battle of Liegnitz, Battle of the Wahlstatt Plain].

Unlike Henry, Baidar knew that Wenceslas was two — and only two — days’ march away. The initial Mongol right flank army is estimated by various sources at 12,000 – 20,000 cavalry, and they had certainly suffered losses in Poland, the extent of which no one even attempts to guess. They were already well outnumbered by Duke Henry’s combined armies of 30,000 cavalry and foot soldiers. An additional 50,000 troops from Bohemia could push the Mongols’ odds of success well past poor down to absurdly bad. Even the best cavalry, organization, command and tactics in the world might not overcome 5-to-1 adverse odds. They knew they had better get this battle done and over with before Wenceslas arrived lest they be overwhelmed, causing Subutai’s northern flank to fail and imperiling the entire Great Western Invasion. The spy network used by the Mongols was unexpectedly (for their enemies) accurate, and they always seemed to know what their foes could and couldn’t do. Knowing that Henry was heading into a plain surrounded by low hills close to Legnica, the Mongols arrived there first.

Upon spotting the Mongols in the distance, already on the plain, waiting, Henry divided his army into four squadrons placed one after the other. The first group, commanded by Bolesław [Boleslav, Boleslaus] son of Děpolt [sometimes called the “Margrave of Moravia”], was composed of knights from assorted nations accompanied by the Goldberg miners who were acting as foot soldiers. Group two, commanded by Sulisław, brother of the late palatine of Kraków, a city now burned to the ground, was of Krakóvians and knights from Welkopole. Group three consisted of Mieszko II the Fat of Racibórz and Opole leading his knights, and Poppo von Ostern from Prussia leading his Teutonic Knights. Group four, led by Duke Henry himself, consisted of soldiers from Silesia and Breslau, knights from Welkopole and Silesia, and French Knights Templar.

Henry II’s reach of power at its greatest extent, 1239.

Source: Wikipedia – Henry II the Pious

The Teutonic Knights and Knights Templar were Christian religious military orders, originating in the Crusades in the Holy Land, who trained and lived under rigorous religious and military training and discipline. They were the cream of the European crop, and Henry had high hopes, high hopes indeed. Orda and Baidar, as usual, simply planned for and expected victory.

In the next installment, we’ll first review the different battle styles of Christian Europeans and Mongols; then the battle begins.

Interactive Google MyMap. Important locations of Winter 1241 CE. Click on any marker or line for description. If map doesn’t display properly in your email, go to the blog.

Entire Mongol Empire & Rus’ Series: Click Here

First Installment: Why didn’t the Mongols Conquer Europe in the 13th Century?

Previous Installment: The Armies Separate || Mongol Empire LXXVII

Next Installment: The Battle of Legnica || Mongol Empire LXXIX

This Installment: Kraków to Legnica || Mongol Empire LXXVIII

Sources

Primary Source for Battle of Legnica: Mongol Invasions, Battle of Liegnitz

Britannica – Oder River Hydrology

MDPI – Oder River Ice Jams

PodBay – Legnica and Mohi

PolishHistory – War of the Worlds at Legnica

ThoughtCo – Legnica, Battle of

Wikipedia – Europe, Mongol Invasion of

Wikipedia – Henry II the Pious

Wikipedia – Kraków, Sack of

Wikipedia – Legnica, Battle of

Wikipedia – Legnica Battlefield (Legnickie Pole)

Wikipedia – Legnica History

Wikipedia – Mongol Invasions and Conquests

Wikipedia – Opole, Battle of

Wikipedia – Opole History

Wikipedia – Poland, First Mongol Invasion Background

Wikipedia – Poland, First Mongol Invasion of

Wikipedia – Poland, First Mongol Invasion Route

Wikipedia – Racibórz

Wikipedia – Racibórz, Battle of

Wikipedia – Vladislaus I of Opole

Wikipedia – Wrocław History