[By Chuck Almdale]

[NOTE: If maps, pictures and legends don’t display properly in your email, go to the blog. Interactive Google maps may not work in your email but will work on the blogsite. There is a link at the bottom to the entire Mongol Empire & Rus’ series.]

Interactive Google Satellite MyMap, modified, Sajó River environs .

The Hungarians Encircled

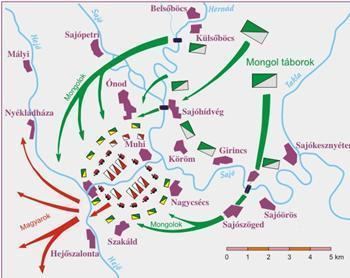

Exactly where the primary battle between the two armies took place is uncertain and as usual, versions differ. Almost certainly the armies met in the open, near the Hungarian camp not far from the Sajó River, somewhere south of the stone bridge. Batu Khan was well outnumbered as Subutai had taken half the army to cross the Sajó to the south. In the initial battles at the bridge over the Sajó and near the Hungarian encampment, many died on both sides. Before Subutai arrived with his half of the army, Batu’s force took such a beating that he considered withdrawing, a nearly unthinkable situation for a Mongol commander. But off to the south and out of sight of the battle, Subutai’s 30,000 troops finally crossed the Sajó, reformed, and raced to the battlefield. The Hungarians, now attacked from the rear by yet another swarm of Tatars suddenly appearing from nowhere, fell back to take refuge within their “fort” of lashed-together wagons and hastily-constructed earthworks. By now it was well past “the second hour of the day” [5:15-6:15 am].

Four miles from Mohi bridge to upstream bridge, five miles to downstream bridge.

Source: NewWorld Enclyclopedia – Battle of Mohi

The Hungarians now found themselves pinned down within their rudimentary fortification. If they could have fallen back all the way to Pest rather than cluster within their circle of wagons, things might have gone far better for them. However, Subutai’s 30,000 troops appearing in their rear probably nipped that thought in the bud. The Hungarian’s “fort” gave them some protection, but the Mongols had them nearly surrounded, with time to bring up any heavy siege equipment or flame throwers they may have brought across the Carpathians.

Archdeacon Thomas of Split in Historia Salonitana continues (pgs. 267-269):

The Hungarians, seeing that they were surrounded on every side by bands of the enemy, lost all sense and reason. They were unable to set their minds to drawing up their forces or to joining a full-scale pitched battle. Dazed at the enormity of their situation, they wandered to and fro like sheep in a sheepfold trying to evade the jaws of the wolf….They did not hold their shields against the storm of arrows and spears, but instead turning their backs they fell, so many everywhere, like acorns scattered when an oak tree is shaken. And when all hope of saving their lives was spent, and death, as it were, passed through the camp gazing in their faces, the king and the leading men, abandoning their standards, turned to seek refuge in flight. Then the rest of the army, terrified at the swift toll of deaths and stunned with fear of the devouring flames all around them, set their hearts on nothing else but flight. But when they sought to snatch themselves from all these dangers by fleeing, they encountered another problem close at hand and on their own side. For the way along the paths had been hazardously impeded by the maze of ropes and the closely pitched tents, and in their haste to run out of the camp, one man trampled upon another, and the numbers brought down by their own fellows falling on them seemed hardly less than those struck down by the enemy arrows.

The Hungarians discovered their water and supplies were insufficient to withstand a siege of any length. The Mongols, the men as tired as their horses, began to bombard the encampment with boulders, flaming arrows, naphtha-soaked cotton and Chinese firecrackers. Gunpowder was new to the Europeans and the explosions were intended more to terrify than to damage or maim. The Mongols were well supplied and could pillage and scour the countryside for more food and water whenever they wished. They could also stay out of range of Hungarian archers while they catapulted their missiles. The Hungarians began to realize their position was untenable; when they spotted a visible gap in the Mongol line, they decided to make a run for it.

The battle of the Sajó River: Mongol encirclement and Hungarian flight through a gap in the Mongol line. Source: Alchetron – Battle of Mohi

Archdeacon Thomas of Split in Historia Salonitana continues (pg. 269):

But when the Tatars perceived that the Hungarian army had turned to flight, they left a door open for them, so to speak, and allowed them to depart. They did not pursue them with all their force, but followed them cautiously, on two sides, not allowing them to turn aside. All over the paths lay the wretched Hungarians’ valuables, their gold and silver tableware, their crimson garments, their wealth of arms.

Unfortunately for the Hungarians, this was another favorite strategy of the Mongols, the “false escape path” which we saw used at the Battle of the River Kalka in 1223 (Part XLVI). When the Hungarians clambered over their tent-ropes, charged through the gaps in their wagon-fort and sped through the space they saw in the Mongol line, they became strung out and disorganized and found themselves surrounded on both sides by long lines of well-armed Mongol cavalry showering them and their horses with arrows.

Battle Tactic: Open the End. Source: Behance – Genghis Khan Military Tactic

Archdeacon Thomas of Split in Historia Salonitana continues (pg. 269):

But the Tatars, with their unparalleled savagery, paid little heed to all the rich plunder, intent only on human carnage. When they saw that their enemies were exhausted from running and unable to stretch out their arms to fight or their legs in flight, they began to rain spears upon them on all sides and to cut them down with swords, sparing no one, and butchering them like animals. Left and right they fell like leaves in winter; the whole way was covered with their wretched bodies; blood flowed like the stream of a river. The hapless country far and wide was red, stained with the blood of her sons. Then the pitiful multitude, those whom the Tatar sword had not yet devoured, by necessity came to a certain marsh. They were not given the chance to take a different way; pressed on by the Tatars, almost the whole of the Hungarians entered the swamp and were there dragged down into the water and the mud and drowned almost to a man. There perished the most illustrious Ugrinus; there perished Matthias of Esztergom and Bishop Gregory of Győr; there many a prelate and crowd of clerics met their fate.

The Hungarian retreat became a panicky rout, as Subutai had planned. The Mongols rode the Hungarians down and killed them with arrow, lance and sword. Losses are frequently estimated at 40,000-65,000 men. Archbishop Ugrin was killed. Prince Coloman was severely wounded but made it back to Pest, King Béla escaped as well. A great number of the ispáns, ecclesiastics and noblemen of Hungary were killed. It was a terrific defeat for what was then believed to be the strongest army in Europe. If this was Europe’s best army, many would think, obliterated nearly to a man in a matter of a few hours, so much the worse for the rest of us when the Mongols continue westward to the sea. It was the end of days, the gates of hell had opened and Satan was now taking possession of the earth.

Batu’s victory at Mohi. Source: KafkaDesk – On this day in 1241 the Mongol Horde

Repercussions of the Hungarian Defeat

What made this defeat even more crushing for Christian Europe was that it came only two days after the immense defeat of combined Polish and German forces by the Mongols at Legnica. Two days!

Duke Henry’s Silesian army was destroyed at Legnica on April 9th; King Béla’s Hungarian army obliterated on April 11th. As the news quickly spread throughout Europe, people were stunned and terrified. How many Tatars were there? Millions? How soon would they appear at our gates? Tomorrow? The Poles and others thought that supernatural powers were at work, or that Mongols weren’t exactly human. Perhaps this was Armageddon and they were a demon army pouring out from the yawning gates of hell, or even unleashed by the hand of God as punishment for the European’s innumerable sins. Genghis Khan had once said words to that effect:

I am the punishment of God…If you had not committed great sins, God would not have inflicted a punishment such as me upon you.

— Genghis Khan

Well…maybe Genghis Khan said that, or something like that. What is certain is that the Mongols were very human. They simply had excellent training, discipline, efficiency and order, four qualities European armies then lacked. They also had wonderful horses with great endurance that would find their own food in the fields. Their archers — and all Mongolian men were archers from the moment they could pick up a bow — could shoot with accuracy from the back of a galloping horse without needing to hold the reins. They enjoyed riding, hunting, battle, looting, taking slaves and concubines, and outwitting, harassing and terrorizing the settled peoples of the world. These are qualities shared to varying degrees by all peoples everywhere, since long before human history began. The Mongols, in their day, put these qualities together better than anyone else.

Size of the two armies

As said above, versions of this battle differ, especially when it comes to estimates of the sizes of the two armies. The tendency seems to be to inflate the size of the army you do not support; this makes the Mongol victory even more stupendous, or the Hungarian loss more inevitable. The contemporaneous account of German Epternacher Notiz reported Hungarian losses at 10,000 men; as their loss of men was nearly total, the army also around 10,000 men. From the Mongol side, Historian Rashid al-Din numbered the entire Mongol force invading all of Central Europe at 40,000 cavalry, only some of them at Mohi. Juvayni, also from the Mongol side, numbered the Mongol “reconnaissance force” at 10,000 and the Hungarians at 20,000. Mongols themselves claimed the Hungarian army was twice as large as theirs. Wikipedia frequently says Hungarians numbered 60,000-80,000. HistoryNet.com says: Hungarian forces numbered 60,000-70,000, of which they lost 40,000-65,000; Mongolian forces numbered 50,000 for the main and Transylvanian flank armies, and 20,000 in Poland. Britannica says Hungarians lost 60,000 of 100,000 men, and Mongolian losses out of 80,000 men are unknown. Other sources say Mongols numbered 200,000 and Hungarians 400,000. One chronicle claims 500,000 Mongols for the entire invading force. Sam Djang in Genghis Khan: The World Conqueror says the entire invading force was around 150,000; 30,000 stayed in Russia/Kiev, 20,000 went to Poland, leaving 100,000 for the central and southern Hungarian invading forces. Some sources estimate that whatever their sizes, Hungarians outnumbered the Mongols two-to-one. Others think they were roughly equivalent. This will likely never be settled, so choose your side and pick the numbers you like; someone, somewhere will agree with you.

Burial Site at Mohi In Eastern Hungary (Photo: Sebastian Mrozek).

Source: Europe between East and West – King Bela

Entire Mongol Empire & Rus’ Series: Click Here

First Installment: Why didn’t the Mongols Conquer Europe in the 13th Century?

Previous Installment: Dawn on the Sajó River || Mongol Empire XCII

Next Installment: The Siege of Pest || Mongol Empire XCIV

This Installment: Battle at the Sajó River || Mongol Empire XCIII

Sources

History of the Bishops of Salona and Split (Historia Salonitana), Archdeacon Thomas of Split; General Editors: János M. Bak, Urszula Borkowska, Giles Constable, Gerhard Jaritz, Gábor Klaniczay; Central European University Press, 2006 Budapest and New York. Link to free PDF.

Mongol Invasion of 1241 and Pest in Hungary, The; János B. Szabó; Academia.com. Link to free PDF.

Britannica – Mohi, Battle of

HistoryExtra – Medieval, Genghis Khan Warlord

HistoryNet –Mongol Invasions, Battle of Liegnitz

HistoryNet –Mongols on the march & logistics of grass

MilitaryHistoryFandom – Mohi, Battle of

NewWorldEnclyclopedia – Mohi, Battle of

Substack – Mohi (1241), Battle of

WeaponsAndWarfare – Sajó River, Battle of

Wikipedia – Batu Khan

Wikipedia – Carmen Miserabile

Wikipedia – Central Europe, Mongol Invasion of

Wikipedia – Holy Roman Empire, Mongol Incursions into

Wikipedia – Hungary, First Mongol Invasion of

Wikipedia – Mohi [Sajó River], Battle of

Wikipedia – Mongol Invasions and Conquests

Wikipedia – Sajó

Wikipedia – Subutai

ZCMS.Hu – Muhi, Battle of

You must be logged in to post a comment.