[By Chuck Almdale]

[NOTE: If maps, pictures and legends don’t display properly in your email, go to the blog. Interactive Google maps may not work in your email but will work on the blogsite. There is a link at the bottom to the entire Mongol Empire & Rus’ series.]

Spread of the Mongol Empire 1206-1294 CE.

Source: Wikipedia – Mongol Empire

Introduction to the Four Theories of Withdrawal from Central Europe

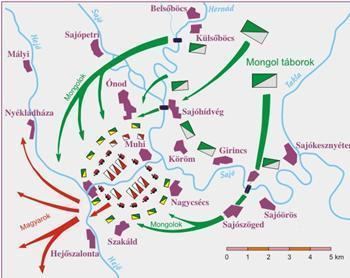

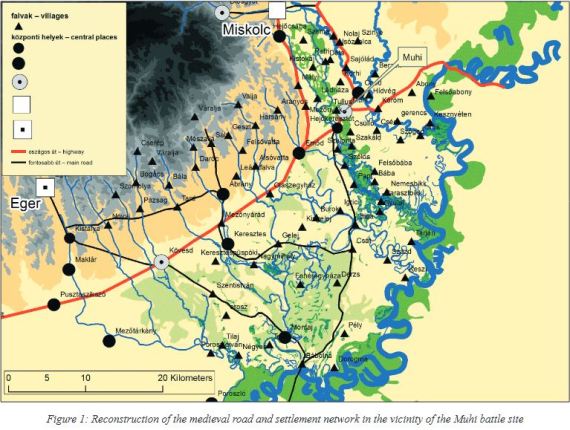

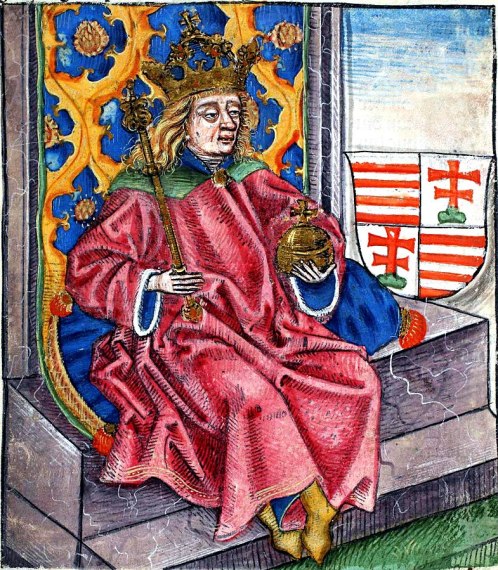

Over the past eight centuries historians, politicians, military theorists, and the randomly curious — especially those in the West — have read about and speculated upon this question: Why didn’t the Mongols conquer all of Europe? Why did they reach the Danube River in central Hungary, stop and turn around? Genghis Khan had stated his intention to continue his conquest of the world all the way to the western sea, or for his family and empire to complete the task should he die first. Ögedei, his second son and successor as Khagan (reigned 1229-1241), commissioned Batu Khan and General Subutai to carry out this mission through Europe to the shore of the western sea. In 6 ½ years, from 1236 to mid-1242 CE they conquered over half of Europe — the portion from the Ural Mountains to the eastern border of the Holy Roman Empire. Their army was reduced yet still large. They lived off the land and the locals, receiving no supplies or reinforcements from Mongolia. Some sieges took longer than expected, and the battle at the Sajó River [Mohi, Muhi] in Hungary was touch and go for a few hours. King Béla IV of Hungary had thereafter eluded their grasp and appeared able to continue to do so indefinitely. The European armies so far appeared ill-led, disorganized and ineffectual. Nearly everything looked good. Had they continued west and taken over Europe, as the terrified Europeans of the time fully expected, Eurasian world history would be completely different and what the world would look like today is anybody’s guess. Why did they pack up their gers and head back east?

My final installments in this series look at the historical analysis of the Mongolian withdrawal from Hungary. Over the course of centuries many books and millions of words have been written on this particular question. I wish to address this problem with the greatest efficiency [read: succinctly] yet still touch upon most of the pertinent facts and theories on all sides of the discussion, thereby giving the reader something more than the naked unsupported opinion of an historian or myself. After reading many sources, papers and websites, I will focus on the best analysis I could find. This is the work of historian Stephen Pow, specialist on the Mongol Empire, and consists primarily of his master’s thesis for the University of Calgary, “Deep ditches and well-built walls: a reappraisal of the mongol withdrawal from Europe in 1242.” [Link to free thesis PFD]

Most of what follows over the next eight postings will consist of a significant abridgement of Pow’s thesis paper. Major digressions by me from Pow’s work will be denoted with “– CA comment”.

What is the object of defense? Preservation. It is easier to hold ground than take it. It follows that defense is easier than attack, assuming both sides have equal means. Just what is it that makes preservation and protection so much easier? It is the fact that time which is allowed to pass unused accumulates to the credit of the defender.

— Carl von Clausewitz, On War

In the middle of June 1241, less than four months since the Mongol army had crossed his eastern border and less than three months since they had obliterated his Hungarian army at Mohi, Hungarian King Béla IV was hiding in Zagreb, Slovenia, busily writing letters to the Pope, the Holy Roman Emperor, the King of France and anyone else he could think of that might help his conquered and beleaguered kingdom, now filled with pillaging Mongols murdering everyone in sight. At the same time a German chronicler wrote: “In this year, the kingdom of Hungary, which had existed for 350 years, was destroyed by the army of the Tartars.” It certainly seemed that way. Yet by June 1242 the Mongols had completely withdrawn southeastward to Bulgaria and a few months later were back in the Wild Fields a thousand miles east of Pest. Explanations abound as to why, none of them fully satisfactory.

In 1996 historian Greg S. Rogers wrote “An Examination of Historians’ Explanations for the Mongol Withdrawal from Central Europe,” providing the first systematic overview of these historical theories, outlining their support found in the sources and criticism they’ve received. Pow (pgs. 9-10) notes Rogers’ observation that “…there is something paradoxical in that the Mongol withdrawal is supposed to have “saved Europe,” and yet a general history of the Mongols or Eastern Europe will devote no more than a few sentences to the how and why of Europe’s salvation.” Most historians have cited secondary source material alone as support, omitting primary sources which may agree or contradict, sometimes both. Rogers’ analysis arrived at four major theories used to explain the withdrawal.

The Four Theories of Withdrawal from Central Europe

1. The limited goals / gradual conquest theory. The invasion of Europe in 1241 was never intended as conquest but only as an exploratory raid: the “gradual conquest.” Pow expands this description to “limited goals,” adding the argument that Batu Khan invaded Hungary only to punish King Béla IV for harboring Cuman refugees whom he considered his property by right of conquest.

2. The political theory. The news of Khagan Ögedei’s death in Mongolia on December 11th, 1241 was received by Batu in March, 1242 during the Hungarian campaign. Batu immediately ordered his forces to evacuate Europe in order to fulfill his role in the Khagan succession crisis. Without doubt this is by far the most common explanation offered in any general overview of the Mongol Empire.

3. The ecological / geographical theory. The Hungarian plain offered insufficient pasturage for the Mongols’ enormous herds of horses. Therefore they concluded that Europe in general was unsuitable for conquest. Returning to the Kipchak steppe, the Mongols gave up further westward expansion of their empire because of these ecological constraints. [This category was later expanded to include temporary climatic factors.]

4. The military weakness theory. The Mongols were so badly weakened from subjugating the Kipchak steppe, Volga region and Eastern Europe that they could not continue their conquests and withdrew from central Europe.

Understandably, the terrified Europeans of the time thought far less about why the “Tatars” left than where they’d come from and how soon they’d return to destroy everything. The most frequent answers at the time were “from the gates of Hell” and “all too soon.” Alone among contemporary western observers, John of Plano Carpini in his “History of the Mongols” wrote that God killed the Great Khan to stop their advance and save Europe. Other observers of the time assumed they’d soon return to finish the job. More common was Archdeacon Thomas of Split’s sentiment that the invasion was God’s punishment on Hungary for the people’s sins. To others they were forerunners of the End Times, Ishmaelites or Gog and Magog. But within a few years these flights of fancy were brought back to earth when several friars returned from visits to Karakorum in Mongolia with this information: The Mongols were neither demons nor signs of the apocalypse but unknown barbarians from the Far East who remained a threat to the West.

Pow then addresses the theories in order and dismisses the possibility that more than one of them is true (pg. 12):

“… it does not make sense to imagine that it was some combination of the existing theories which brought about the withdrawal, since these theories often contradict each other on fundamental points, such as the actual intent of the Mongol leaders when they invaded Europe. As Rogers notes, the existing theories diverge so widely it would be difficult to convince someone that their differences are superficial rather than genuine.”

Looks crowded, doesn’t it, but locations differentiate as you zoom in. Interactive Google MyMap above shows all locations for Rus’ 9th-13th centuries and Mongol Eastern and Central European invasion 1236-42 CE. Click on any marker or line for description. If map doesn’t display properly in your email, go to the blog.

The Limited Goals Theory of Withdrawal from Central Europe

The limited goals theory as presented by Pow (pgs. 34-41) has two alternatives: the Mongols were punishing the Hungarians for giving sanctuary to the Cumans fleeing the Mongol conquest in the steppe; the Mongols were exploring for a future invasion. Either way their goals were limited, they never intended to stay and they left when they’d achieved their objective.

Cumans arrive in Hungary 1239, from 14th century Chronicum Pictum.

Source: Wikipedia – Köten

Punishment for Sanctuary for Cumans

Many historians, especially Peter Jackson in his The Mongols and the West, argue that Batu invaded Hungary as punishment for their giving sanctuary to the Cumans fleeing the Mongol conquest in the steppe. Once their punishment was meted out, they left. The basis for this is a line within Batu’s repeated requests for King Béla IV to submit. This request was sent three times; the text may have remained the same or differed slightly. Batu wrote (Pow, pg. 35):

“I have learned, moreover, that you keep the Cumans, my slaves, under your protection; and so I order that you do not keep them with you any longer and do not have me as an enemy on their account.”

When Mongols conquered a people, they considered themselves owner of all the land and the people conquered. Some of the conquered people — usually 10% — would be enslaved. In 1238-1240 the Cumans fled their lands westward and found sanctuary in Hungary rather than remain and be conquered by the Mongols, so one could reasonably assume that Batu Khan might wage war on anyone who took something — the Cuman people — he considered his own property.

Contradicting this argument to some extent is the report of Friar Julian [Julianus barát] who left Hungary in 1235 CE searching for the homeland of the Magyars [now the Hungarians, different from the Hungarians of Attila the Hun], known as Eastern Hungary [Eastern Magyars, Magna Hungaria, Great Hungary]. He located it between the Volga River and the Ural Mountains in an area later called Bashkiria and Bashkortostan, and found their languages mutually intelligible, despite a separation of some 300 to 400 years. On his 1237 return to Hungary via the northern Rus’ principalities, he carried a message from Batu Khan back to King Béla IV requesting Bela’s submission, which Béla ignored. While there had been some battles — well short of an attempt at conquest — between the Cumans and Mongols, particularly in 1223 when Generals Jebe and Subutai passed through the area, the major battles causing the Cumans to flee en masse occurred a year later in the autumn of 1238. If the Cuman flight to safety in Hungary was the reason for Batu’s invasion, when the first submission request was sent in 1237 the Cuman flight had not yet happened.

Local autonomies in Hungary late 1200s, including Cumania and Jászság (Eastern Iranian people). Source: Wikipedia – Kunság

Additionally Batu’s final request for submission (and perhaps all requests) alluded to the promise of the Eternal Blue Sky God, Tengri, as channeled by the Mongol shaman Kokochu [Teb Tengri], that “the entire earth” was given to Genghis Khan and his family to rule. Batu wrote (Pow, pg. 37): “I am aware that you are a wealthy and powerful monarch … Hence it is difficult for you to submit to me of your own volition; and yet it would be better for you, and healthier, were you to submit willingly.” This is request for surrender, the acceptance of vassal status, the paying of tribute, and assisting in Mongolian wars. It has nothing to do with punishment for aiding Cumans.

Laying Groundwork for Future Invasion

Rogers held that the limited goals theory of exploring and terrorizing in preparation for future invasion has received little criticism because no one save its supporters even bother to mention it. He finds the limited evidence supporting it unconvincing. For example, a Russian chronicle is cited which mentions that the Mongols took grain prior to invading Hungary in order to provision themselves during the return journey. However, many have commented that the Mongols were nomadic pastoralists, ate little grain, and did not use it as fodder for horses. Ibn al-Athir observes (Pow, pg. 35):

“The Tartars do not need a supply of provisions and foodstuffs, for their sheep, cattle, horses and other pack animals accompany them and they consume their flesh and nothing else.”

Historians Hungarian László Makkai and Soviet V.P. Shusharin, hold that the purpose was terrorism preparing the ground in advance of invasion. Until the Rus’ and steppe territories were firmly under Mongol control, additional conquests were impossible. They point to the raids in China, the successive invasions of Korea and the Caucasus, and Jebe and Subutai’s campaign two decades earlier through the Caucasus, Volga and steppe region as evidence that Mongols first explored, then conquered. But the early raids into China were just that, writes Pow, raids for the purpose of pillaging; only in retrospect do they seem preliminary to conquest. Later raids in China occurred while the bulk of the army was fighting in Khwarazmia and their forces in China were insufficient for conquest and control. The Mongols repeatedly conquered Korea and received vows of submission and promises of tribute; as soon as they left to fight elsewhere, the Koreans reneged and had to be re-invaded and re-conquered. Jebe and Subutai in the Caucasus and southern Rus’ in the 1220s may have been on a mission of conquest, but their force was totally inadequate to retain any territories gained. The Mongols reportedly left 30,000 troops in Rus’ for organization and control of the newly conquered territories while the rest of the army marched into Poland, Transylvania and Hungary. Jebe and Subutai had only 20,000 men to begin with, and probably far fewer by the time they arrived back in Mongolia. Additionally, that expedition may have begun as exploration but then ended as reconnaissance after Jebe and Subutai considered the desirability of returning with a much larger army. In Hungary in 1241, they already had their much larger army with them.

The Secret History of the Mongols reveals that the expedition was considered a serious undertaking. All the members of the Jochid branch were present, plus members of the other three branches. Pow writes (pgs. 37-38):

Ögödei released a proclamation through the empire that the eldest sons of any prince or officer were to be sent on the campaign. This was on the advice of Chaghadai, who suggested, “If the eldest of the sons goes into the field, the army will be larger than before. If the troops who set forth are numerous, they shall go to fight looking superior and mighty.” Rashid al-Din claims that Ögödei himself wanted to take part until Möngke convinced him to remain in Mongolia. Still, the army contained Sübetei, the greatest living general in the Mongol army, the entire Jochid dynasty, and sons of Ögödei, Chaghadai, and Tolui, including two future great khans. Möngke and Güyüg were recalled before the army continued against Hungary, but it still contained enough Chinggisids that it is hard to believe its intentions were anything short of conquest.

The Muslim chroniclers saw it as conquest. Rashid al-Din, writing around 1300 CE comments that Poland and Hungary were conquered but later rebelled. He adds that Chinggis Khan had issued an edict that Jochi should (Pow, pg. 38) “seize and take possession of all the northern countries.” But Jochi died even before his father Chinggis Khan, so Jochi’s son Batu took on the task.

According to Pow (pg. 39), Rogerius stated that following their victory at Mohi, the Mongols “set aside Hungary beyond (east of) the Danube and assigned their share to all of the chief kings of the Tatars who had not yet arrived in Hungary. They sent word to them of the news and to hurry as there was no longer any obstacle before them.” This looks like distribution of lands [“appanages”] to family members. Rogerius also reported (Pow, pg. 39) “the Mongols had intended to invade Germany in the spring of 1242, but that they abandoned these plans.” And returning to Friar Julian, Pow writes (pg. 39) that he “…met the ruler of Suzdal who warned him of the Mongols’ expressed intentions to conquer not only Hungary, but Rome and the land to the west of it…” Finally, around the same time the Mongols (likely Batu) sent a submission ultimatum to Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II. You don’t do that if you are not planning to continue the conquest. The Mongols always sent polite requests for submission to those they intended to conquer. If it was accepted, battle was averted, the taking of loot, slaves and annual tribute would be assured and Mongol lives would be saved.

Interactive Google MyMap above shows all locations for Central Asian conquests 1220-1224 CE. Click on any marker or line for description. If map doesn’t display properly in your email, go to the blog.

Entire Mongol Empire & Rus’ Series: Click Here

First Installment: Why didn’t the Mongols Conquer Europe in the 13th Century?

Previous Installment: The Mongols in Bulgaria || Mongol Empire CVI

Next Installment: The Political Theory of Withdrawal || Mongol Empire CVIII

This Installment: The Limited Goals Theory of Withdrawal || Mongol Empire CVII

Source

Deep ditches and well-built walls: a reappraisal of the Mongol withdrawal from Europe in 1242; Pow, Lindsey Stephen, 2012; Department of History, University of Calgary, Calgary, Canada. Link to free thesis PDF.

You must be logged in to post a comment.