[By Chuck Almdale]

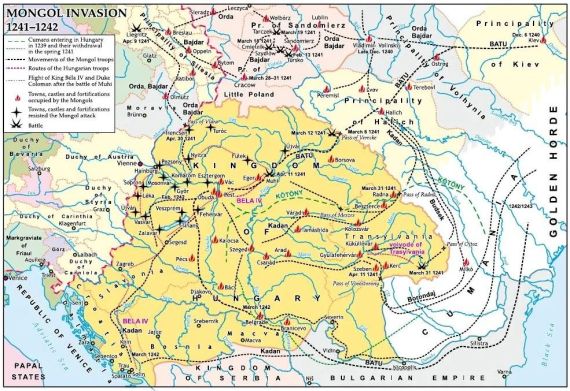

[NOTE: If maps, pictures and legends don’t display properly in your email, go to the blog. The interactive Google map within this posting works on the blogsite, if not in your email. There is a link at the bottom to the entire Mongol Empire & Rus’ series.]

Battle of Legnica (Legnitz) 1241. From Legend of Saint Hedwig: “Here Duke Henry, the son of St. Hedwig, is in battle with the Tartars in the field which is called Wahlstatt“; unknown artist, 1353. Medieval illuminated manuscript , collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum.

Source: Wikipedia – Warfare in Medieval Poland

Battle Styles: European Vs Mongol

The typical European army of the 13th century was poorly organized and poorly trained. They consisted of squadrons of irregular sizes and purpose, with little planned strategy beyond get close to your foe and bash them to pieces one at a time. The Battle of Agincourt, when Henry V of England defeated a far larger army of France with tactics, field position, troop discipline and longbows raining arrows upon their enemies was still 174 years into the future. On 9 April, 1241 CE when the Battle of Legnica commenced, command was based on birth and status, not competence, and displays of personal bravery and honor were critically important to the knights. Even if they lost, a brave fight brought personal honor. If slain while in the act of defending damsels or nations, they’d gain a good seat in Heaven.

A European knight armed and ready for combat – reenacted. The 33rd photo in a series which shows the knight, with a lot of help, donning his many-layered gear. Source: CatherineHanley – Arming a knight in the 13th century

Mongol cavalry units on the other hand were supremely organized into multiples of 10: ten men in an arvan, ten arvan in a zunn, ten zunn in a Mingghan, ten mingghan in a tümen, and as many tümen as you had available in an army. Each unit of any size from 10 to 10,000 men had its own designated leader. Discipline was high, infractions punished, battle commands signaled by colored flags and/or drumbeats. Everyone knew what to do, how to issue and follow orders, and the top general planned it out ahead and orchestrated it all. A commander could be anywhere he saw fit in his formation so as to observe and make rapid decisions. European commanders — on the other hand — fought alongside their troops, easily identified, usually in danger, and unable to create opportunities or respond to developments.

Mongol light archer. Source: Quora – Genghis Khan’s role in Middle East

The goal of Mongol battle was twofold — win and keep the cost of battle low; today we might say maximize gain, minimize cost. The Mongols were far from home and hauling their own supplies; they must efficiently kill or defeat an enemy with as little loss to themselves as possible, as unexpected reinforcements weren’t going to suddenly appear to save the day. Their strategies were often based on the Mongolian method of hunting game; lead your prey into a prearranged trap, attack from all sides, kill them quickly, kill them all. This was the essence of their favorite strategy, the feigned retreat — a tentative or mocking pseudo-attack, then false flight, then ambush, surround and massacre. Foes interested in bravery and valor would never intentionally appear cowardly and flee before an enemy, and it took time for valorous warriors to even conceive that someone else might concoct a tactic that was so…well, downright dishonorable.

Mongol heavy lancer – Six of every ten Mongol troopers were light cavalry horse archers; the remaining four were heavily armored and armed Lancers.

Source: Pakistan Defense – Defense-PK

European knights and their large horses were heavily armored, weighing 70 pounds or more. They carried lances to plow down their foe like a battering ram and heavy broadswords to chop them into pieces in close man-to-man battle. Foot-soldiers closely followed the cavalry and killed anyone unhorsed or alive.

Eastern European warriors, 13th century.

Source: DefensePK – Kalka River Battle

Mongols used foot soldiers only when they conscripted (aka enslaved) losers from a previous battle into their army; these men typically were placed in the front lines where they bore the brunt of besieging a city. Most Mongol cavalry wore far less armor than Europeans – only the helmet was metal, the rest was leather – with loose silk underwear that followed an arrowhead into the wound, allowing it to be easily extracted backwards without additionally tearing the flesh. [If you’ve ever had a fishhook extracted from your arm you’ll know what that entails.] Their primary weapon was a recurved composite bow which could fire an arrow 300 yards and easily aimed in all directions, even to the rear; each archer carried 60 arrows of different sorts. Some cavalry wore heavier armor and carried spears for special purposes, such as unhorsing the foe or tripping their horses. Their horses were smaller, lighter and had enormous endurance. They could also find their own food in the wild fields, so the army did not have to carry or continually gather many tons of fodder for their mounts — an enormous logistical advantage. Each soldier had two to four horses and when one tired, would switch to another. In the false retreat strategy, the Mongols would often lure the enemy to where their extra horses were waiting out-of-sight, and attack their tired foe on fresh mounts. Europeans had never encountered such training and tactics, whereas Mongols had beaten European-style forces countless times, and other-styled forces perhaps thousands of times.

Mongol heavy cavalryman and equipment. 40% of Mongol troopers were heavily armored and armed lancers. Source: DefensePK – Kalka River Battle

Mongol armies were adaptable and learned quickly. Any tactics or equipment used by their foes and unfamiliar to them were immediately examined and adopted if obviously useful. Battering rams, catapults, covered siege ladders, flaming arrows, naphtha bombs, gunpowder, undermining walls, redirecting rivers and streams, destroying dams, forced conscription of defeated soldiers to do heavy labor like filling in moats around walled cities; all these were learned from their defeated foes, particularly the Chinese. So useful were the Chinese in inventing, designing and building battle equipment that for their Khwarazmian Empire battles, the Mongols simply conscripted weapon engineers in China and brought them along into central Asia. These Chinese engineers were kept very busy.

60% of Mongol troopers were light archers. Source: DefensePK – Kalka River Battle

The Battle Begins

When the battle on the Wahlstatt plain began on 9 April 1241, the Mongols moved without battle cries or trumpets, transmitting signals by silent flags. Their formations appeared loose, and when Boleslaw’s first squadron charged into them, the Mongols flowed away like water, out of harm’s reach, and showered them with extremely accurate arrows fired from their saddle backward as they fled. The other three Polish divisions did nothing but watch and wait their turn, and Boleslaw’s men fled back to the Polish side.

Fabian Tactic: When enemy is strong, Mongols horsemen disperse & avoid contact; when enemy moves to a weaker position (e.g. after a Mongol feigned retreat), Mongols regroup and attack. Source: Behance – Genghis Khan

Led by Sulisław, Mieszko II the Fat and Poppo von Ostern, the second and third divisions charged. In apparent terror, the Mongols turned tail and fled. Smelling victory the knights pursued, eager to use their lances and broadswords on these dishonorable and diminutive Tartar cowards. Something strange then happened.

From the fleeing Mongols came a single rider who rode around the Polish knights shouting in Polish, “Byegaycze! Byegaycze!” (“Run! Run!”) The Poles couldn’t tell if he was a Mongol performing a ruse or a forcibly conscripted conquered Russian giving the Poles a warning.

The following excerpt comes from Jan Długosz’s account, whose chronicle is the major source of information we have about the battle of Legnica.

There was in their [Mongol] army among other banners one of enormous size….at the top of its spar, there was a figure of a very ugly and monstrous head with a beard, so when the Tartars moved back two miles or so and started to flee, the ensign carrying the banner started to wave the head with all his might, and immediately some thick vapour burst out of it, smoke and a wind so stinky that when this deadly smell spread among the troops, the Poles, fainting and barely alive, stopped fighting and became unable to fight.

— Jan Długosz’s account of the battle of Legnica, cited by PolishHistory

The Opole squad of Mieszko II the Fat was the first to panic. Mieszko took this “warning” at face value and led his knights off the battlefield. Seeing his 21-year-old cousin fleeing, Henry II said: “A great misfortune has come upon us,” and he moved on the enemy with his own troops. Those were his last recorded words. He attacked the Mongols with his fourth division and engaged them in close combat. The Mongols fought fiercely, then again fled, again pursued by the Polish knights. The chase led the knights far out in front of their unmounted support foot soldiers.

NOTE: Want more information on the Mongol style of battle? The website Defense.PK – Battle Report Kalka River has the best discussion of Mongol battle and equipment information, plus great artwork, that I have found on the web. Highly recommended! That this site comes out of Pakistan seems quite odd to me.

A Familiar Story

As HistoryNet puts it, obscuring smoke began to drift across the battlefield from somewhere behind the Polish knights and their now far-to-the-rear foot-soldiers could not see what next happened.

Mongol horse archers had deadly accuracy even while galloping.

Source: DefensePK – Kalka River Battle

It was a typical false retreat and as always, it worked. Once the knights were far enough from their infantry, the Mongol cavalry swept out to both sides of the knights, now strung out and disarrayed, and showered them with arrows. Other Mongols sprang from hiding. If the arrows failed to bring down an armored knight, they shot his horse out from under him. Once dismounted, the heavily armored knights were nearly helpless, and the Mongol heavy cavalrymen with lances and swords slayed them with impunity. The determined, religious and trained Knights Templar made their stand, and every one of them died.

The main Catholic military orders of monastic-knights, a Knight Templar in the middle. In the medieval period the Knights of Malta (“Malte”) were known as the Hospitallers or Knights of Saint John of Jerusalem.

Source: MedievalWarfare – Templars

Duke Henry was gravely wounded and tried to gallop off the field, accompanied by his knights who struggled, and failed, to carry him to safety. When the Mongols fell upon him he was still alive as they pulled him aside and cut off his head. [Another version says Henry was executed after the battle]. They put Henry’s head on the end of a spear and paraded it before the Polish troops in an unsuccessful attempt to make them surrender. One version says the gruesome trophy was then sent to Batu Khan’s camp [which was far away in Hungary at this time; if it went anywhere, more likely it went to Orda or Baidar’s camp].

According to this site, when Henry’s headless body was found on the battlefield, stripped of armor and clothing, only his wife Anna could recognize the body and then only by a distinctive mark: he was polydactylous and had six toes on his left foot.

This trait was confirmed almost six hundred years later when his tomb was opened in 1832. A century later German scientists took Henry’s body from his tomb for laboratory tests, hoping to somehow prove that Henry II the Pious was an Aryan. The body was never returned.

Knight Templar and Knight Hospitaller stained glass window Saint Andrew’s Church, Temple Grafton, Stratford district, Warwickshire, England. Source: MedievalWarfare – Templars

Following their [sometimes] custom of counting the enemy dead, the Mongols filled nine sacks with ears cut from the dead. Polish records say 25,000 men were killed. The Grand Master of the Knights Templar wrote of the battle to King Louis IX of France:

The Tartars have destroyed and taken the land of Henry Duke of Poland, …with many barons, six of our brothers, three knights, two sergeants and five hundred of our men dead.

— Cited by HistoryNet

The Grand Master added that no army of any significance now stood between the invaders and France. That was no exaggeration. King Wenceslas (the “One-eyed”) of Bohemia (modern-day western Czechia) was still one day away from the battle. After hearing of the slaughter of his brother-in-law and his army, Wenceslas returned south to Bohemia, gathering reinforcements from Thuringia and Saxony along the way, and hoped Bohemia’s mountainous terrain would discourage the Mongols from attacking his kingdom.

King Louis IX, according to many sources, began to make preparations to go to central Europe to fight the Mongols, and told his mother, Queen Blanche, that “either they would send the Tartars back to hell, or the Tartars would send them to Paradise.” His use of “Tartar” was a play on the word Tartarus, in Greek mythology a pit of torment lower than Hades; Christianity modified Tartarus into the place rebelling angels were sent. This is one of several sources cited as the origin of the exonym Tartar or Tatar — still used today — for the Mongols’ in particular and central Asians in general.

Holy Roman Empire 1273-1378 CE between France, Poland and Hungary; Northern March, Brandenburg and Saxony in upper right.

Source: Wikipedia – Margraviate_of_Brandenburg

It was still 9 April, 1241 when the battle was over and done. Despite King Louis’s fears, the Mongol army in Poland had no intentions of continuing even 50 miles westward into Lusatia, Saxony or the Northern March, all regions of the Holy Roman Empire, let alone 600 miles to Paris. Their remit was to so distract the Poles that they would not consider sending aid to Hungary. That done and knowing full well that a large Bavarian army was in the vicinity, the Mongols quickly set off for Hungary. This journey did not go as smoothly or quickly as they wished, and some interesting details of Bohemian and Moravian history came about as a result.

Interactive Google MyMap. Important locations of Winter 1241 CE. Click on any marker or line for description. If map doesn’t display properly in your email, go to the blog.

Entire Mongol Empire & Rus’ Series: Click Here

First Installment: Why didn’t the Mongols Conquer Europe in the 13th Century?

Previous Installment: Kraków to Legnica || Mongol Empire LXXVIII

Next Installment: Legnica to Moravia || Mongol Empire LXXX

This Installment: The Battle of Legnica || Mongol Empire LXXIX

Sources

Primary Source for Battle of Legnica: HistoryNet – Mongol Invasions, Battle of Liegnitz

DefensePK – Kalka River Battle

GreekGodsAndGoddesses – Tartarus

PodBay – Legnica and Mohi

PolishHistory – War of the Worlds at Legnica

ThoughtCo – Legnica, Battle of

Wikipedia – Europe, Mongol Invasion of

Wikipedia – Henry II the Pious

Wikipedia – Legnica, Battle of

Wikipedia – Legnica Battlefield (Legnickie Pole)

Wikipedia – Legnica History

Wikipedia – Mongol Invasions and Conquests

Wikipedia – Poland, First Mongol Invasion Background

Wikipedia – Poland, First Mongol Invasion of

Wikipedia – Poland, First Mongol Invasion Route

You must be logged in to post a comment.