[By Chuck Almdale]

[NOTE: If maps, pictures and legends don’t display properly in your email, go to the blog. The interactive Google map within this posting works on the blogsite, if not in your email. There is a link at the bottom to the entire Mongol Empire & Rus’ series.]

Defenestrations of Prague, painted 1844 by Karel Svoboda (1824–1870). The 30 years war broke out in 1618 when Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II was deposed as king of Bohemia and replaced by Protestant Frederick V of the Palatinate. In May 1618, Protestant nobles led by Count Thurn met in Prague Castle with Vilem Slavata and Jaroslav Borzita, two Catholic representatives of the Emperor. In what became known as the Third Defenestration of Prague, both men were thrown out of the castle windows along with their secretary Filip Fabricius, although all three survived. Source: Wikipedia – Defenestrations of Prague

17th Century Miracles

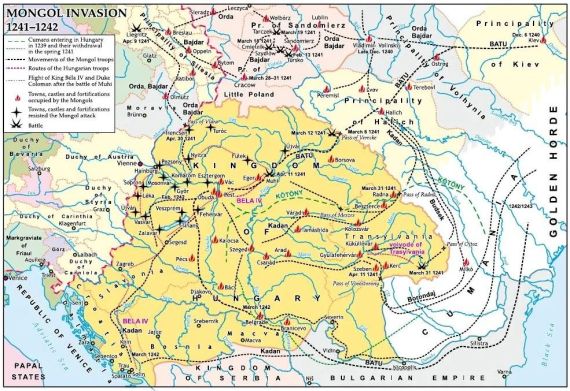

In 1620 the Thirty Year’s War caused the population of the Kingdom of Bohemia to shift from a mixture of Catholics and Protestants to Catholics-only. Pilgrimages to local shrines were encouraged by authorities and the people developed new ways of expressing their spiritual and religious feelings. Throughout this period the Ottoman Empire was a constant threat to central Europe until their defeat in the Austro-Turkish war of 1663-64. Ottoman and Crimean light troops raided Moravia three separate times between 4th September and 7th October 1663. No fortifications fell but the Moravian countryside was heavily plundered and many people were taken prisoner or killed. Constant rumors of Tatars about to arrive kept the people in a state of panic, and the plundering and massacres by Turkish and Crimean Tatars traumatized the Moravians for decades. Shortly after the 1663 raids, three miraculous events appeared in the now 400-year-old story of the Mongol invasion of 1241 and remained important elements in the story for centuries to come (pgs 244-245).

Eastern slope of Hostýn hill, 734 m. (2408 ft.) in Chvalčov in the Zlín Region of Czechia. Photo by Daniel Baránek December 2008. Source: Wikipedia – Hostýn

The hill of Hostýn. In the mid-1600s this hill became a popular destination for Catholic pilgrims for reasons completely unrelated to Mongols. Then in 1663 the following miracle story appeared: In 1241 the Tartars laid siege to a group of Moravians on Hostýn hill. After running out of water and suffering from unbearable thirst the Moravians prayed to the Virgin Mary for help. Not only did she appear to them but she then caused a spring to appear. While they joyously quenched their thirst, the Virgin attacked the Mongols with bolts of lightning, causing them to flee. The story changed a few times after it was written down in 1666, but by the year 1700 it became fixed in form by František Beckovský. Hostýn remained a popular pilgrimage destination until the end of the 18th century when all pilgrimages were banned.

Štramberk, home of the ears. View from Šipka cave with Trúba castle tower above the town. Source: Wikipedia – Moravian-Silesian region

The Hill of Kotouč. Similar to the tale of the hill of Hostýn is that of the town of Štramberk and its hill Kotouč. During the 17th century Štramberk became another center of pilgrimages connected to the fictional defense against the Tartars in 1241. In 1624 Štramberk was given to the Jesuit Convict [a religious— not penal — community] in Olomouc. This Jesuit community supported pilgrimages and a legend was quickly invented concerning the 1241 “Tatar” invasion: Štramberk residents were forced to the top of Kotouč, their local hill, where they prayed to God on the evening before the Feast of the Ascension [40 days after Easter] to save them from the Tatar hordes now surrounding them. God sent a downpour, the roaring waters of which panicked the infidels into flight and the people were saved. A later version, which has since become the most popular, is that the clever people of Štramberk snuck out at night and broke the dams of nearby ponds, drowning out the Tatar camp. In the camp they found nine sacks of ears cut off the heads of defeated Christians (an idea borrowed from Jan Długosz’s chronicle of the Battle of Legnica). Another version from a Štramberk magistrate dates to the 1720s: this time the enemies are Hussites [proto-Protestant followers of Jan Hus] and the year was 1356.

Postcard of Olomouc, Czechia, 1907. Source: Wikipedia – Olomouc

The town of Olomouc was the setting for a third similar myth, dating to 1663 and building on the old myth of Jaroslav of Sternberg, which the local Sternberg family now gladly promoted in local churches which they supported. This legend says that when the “Tartars” besieged Olomouc in 1241, Captain of the City Jaroslav went to Mass before attacking the enemy. After communion was over, there were five remaining pieces of sacramental bread which were wrapped up and carried by a donkey to the battle. With the help of God, Jaroslav defeat the enemy and Jaroslav himself cut off the hand of Peta, the Tartar leader. Peta soon died from his wounds and the Tartars fled to Hungary. After the battle, the priest who unwrapped the sacramental bread found it transformed into the real Body of Christ. He put the body back on the donkey which — all on its own — walked straight to the Jesuit’s Corpus Christi Chapel back in Olomouc. The body is still there today. Jaroslav then founded the church of the Virgin Mary in Olomouc and was generously rewarded by the king. A minor problem is presented by the fact that the Corpus Christi Chapel in Olomouc did not yet exist in 1241. Its future location was until 1454 part of the Jewish quarter which had no Christian church; no matter, it’s a very popular story. The Corpus Christi Chapel in Olomouc was rebuilt in the 1720s with marvelous decorations by Jan Kryštof Handke, including frescoes depicting the legend with the Mongols portrayed as Ottoman Turks.

Corpus Christi Chapel ceiling, Olomouc, painted c.1720 by Jan Kryštof Handke.

Source: UC.UPOL – Corpus Christi Chapel

19th Century Myth Expansion

That was not the end of the myth-making. In 1817 a manuscript fragment was “found” in a church in Königinhof an der Elbe by Václav Hanka, which caused a sensation. Written in Czech and apparently dating from the 13th century, it instantly became the oldest known piece of Czech language literature ever discovered, much to the delight of the newly-born Czech National Revival. Its key element was the poem “Jaroslav” which exalted our hero Jaroslav of Sternberg’s victory over the Tartars in 1241. It also mentioned the miracle of Hostýn.

In 1841, the 600th anniversary of the Mongol invasion into Moravia saw many celebrations, especially in Hostýn and Olomouc, the sites of so many battles and wondrous events. Historian František Palacký — the “Father of the Nation” — gave a lecture in which he used the Jaroslav poem to document and celebrate the importance of the Czech nation. The lecture was published as a book the following year, its fine critical historiography marred only by the fact that Palacký had bought into a document that was later proved to be a complete fraud.

At the end of the 19th century and after many decades of discussion, the entire fragment was conclusively proved to be an elaborate forgery created by its “discoverer,” Václav Hanka himself.

The fundamental problem was the paucity of authentic sources documenting the 1241 invasion. Myths and miracles arose, became popular, were written down and later writers and historians took some of them as factual as they had nothing with which to contradict them. In 1842 Alois Vojtěch Šembera of Moravia edited an almanac on the Mongol invasion which included a treatise by Antonín Boček about the true identification of the hero who defeated the Mongols at Olomouc. Despite the likelihood this event never happened and thus there was no hero, he rejected Jaroslav of Sternberg and replaced him with Zdislav of Sternberg, not a significant improvement. When Boček put out a collection of Moravian sources, he added a few previously non-existent chapters to the third volume of his Codex diplomaticus et epistolaris Moraviae, covering the period 1241-1267, which “proved” how severely the Mongols damaged monasteries such as Rajhrad and cities such as Brno, Benešov, Jevíčko and Uničov. These books became sources for later historians including some now working. Some of these now-exposed forgeries and myths have become something of a national embarrassment and a source of material for Czech humorists.

Interactive Google MyMap. Important locations of Spring 1241 CE. Click on any marker or line for description. If map doesn’t display properly in your email, go to the blog.

The True Passage through Moravia

It the light of all these exaggerations, myths and forgeries, it’s difficult to pick out what — if anything — actually happened as the Mongols made their way from Legnica to Hungary. Historian Tomáš Somer briefly mentions a few likely events [mileage calculations are mine].

The battle of Legnica began and ended on 9 April, 1241. The Franciscan Jordanus mentioned in a letter that the Mongols were in Moravia “some time before the 9th May,” entering through the Moravian Gate just south of Opava. There are reports that by late April they had reached the important Hungarian castle Trenčín [Trentschin, Trencsén], located 110 miles from Ostrava at the north end of the Moravian Gate. This castle was attacked but not taken, although the surrounding countryside suffered heavy damage. The distances involved are not far: From the battlefield at Legnica to Opava is 140 miles, another 20 miles to Ostrava at the north end of the Moravian Gate, 50 miles farther to Olomouc at the south end of the gate, and another 75 miles through the Hrozenkov pass to castle Trenčín. As the Mongols most likely never went to Olomouc at all, the distance from Ostrava to castle Trenčín is 110 miles; from the Legnica battle site to castle Trenčín is a total distance of approximately 270 miles. This could easily be traveled within a week which would put the Mongols at castle Trenčín as early as 16 April; faster, if the Mongols were in a hurry. The only real evidence of actual destruction within Moravia comes from 1247 when the Margrave of Moravia (and future King of Bohemia) Přemysl Otakar granted the city of Opava some economic privileges based upon unspecified damages to the Opava region caused by the marauding Mongol troops some years earlier. The Mongols did not seize any of the fortified places in Moravia and it is a plausible argument that they did not even try to, since they were in a hurry.

Territories that the Premyslids controlled or vassalized in 1301, by Garp27.

Source: Wikipedia – Kingdom of Bohemia

Just how and when Orda and Baidar’s army met up with the Mongol army under Batu and Subutai will be discussed at a later date. Next we will turn to the Mongols southern flank, along the eastern Carpathians and into Transylvania.

Morava River in Olomouc, photo by Poisl.matyas January 2019.

Source: Wikipedia – Olomouc

Entire Mongol Empire & Rus’ Series: Click Here

First Installment: Why didn’t the Mongols Conquer Europe in the 13th Century?

Previous Installment: Moravian Events and Myths: 13th-17th Centuries || Mongol Empire LXXXII

Next Installment: The Mongol Left Flank in Transylvania || Mongol Empire LXXXIV

This Installment: Moravia: 17th Century Miracles || Mongol Empire LXXXIII

Sources

Forging the Past: Facts and Myths Behind the Mongol Invasion of Moravia in 1241; Somer, Tomáš; Zolotoordynskoe obozrenie=Golden Horde Review. 2018, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 238–251. DOI: 10.22378/2313-6197.2018-6-2.238-251. tomas.somer@upol.cz. of Palacký University Olomouc, Olomouc, Czech Republic. Link to free PDF file.

HistoryNet – Mongol Invasions, Battle of Liegnitz

PodBay – Legnica and Mohi

PolishHistory – War of the Worlds at Legnica

Reddit-AskHistorians – Did the Kingdom of Bohemia ever come under attack

ThoughtCo – Legnica, Battle of

Wikipedia – Bohemia & Moravia – Europe, Mongol Invasion of,

Wikipedia – Carpathian Mountains

Wikipedia – Europe, Mongol Invasion of

Wikipedia – Holy Roman Empire, Mongol Incursions into

Wikipedia – Hungary, First Mongol Invasion of

Wikipedia – Kłodzko

Wikipedia – Legnica, Battle of

Wikipedia – Legnica History

Wikipedia – Mongol Invasions and Conquests

Wikipedia – Moravian Gate

Wikipedia – Poland, First Mongol Invasion Background

Wikipedia – Poland, First Mongol Invasion of

Wikipedia – Poland, First Mongol Invasion Route

Wikipedia – Wenceslaus I of Bohemia

You must be logged in to post a comment.