[By Chuck Almdale]

[NOTE: If maps, pictures and legends don’t display properly in your email, go to the blog. Interactive Google maps may not work in your email but will work on the blogsite. There is a link at the bottom to the entire Mongol Empire & Rus’ series.]

Interactive Google MyMap showing all European locations so far mentioned for the Rus’ 860-1235 CE and Mongol Great Western Invasion, 1235-1241 CE. Click on any marker or line for description. If map doesn’t display properly in your email, go to the blog.

The Mongol Invasion Force into Central Hungary

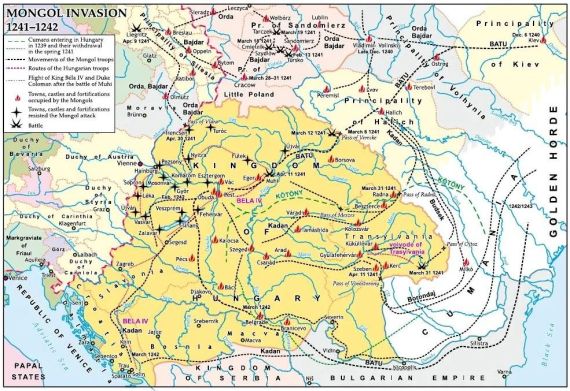

After looking at the strategy for the invasion of Hungary in some detail over the past fourteen installments — the overall strategy, the right flank movements in Poland, the left flank movements in Transylvania and the southern Great Hungarian Plain — we’ve arrived at the Mongolian main attack into the heartland of the Kingdom of Hungaria.

The initial size of the Mongolian Great Western Invasion army in 1236 CE varies between sources, and we’ve been using the commonly cited number of 15 tümans, or 150,000 men. Each man had two to four horses and all his personal weaponry and gear. The army carried enough food to get everyone through the winter seasons of battle when rivers were frozen and crossable, and ten-man gers served as portable folding shelters. Pillaging and tribute from conquered people restocked their supplies and satisfied their needs as the campaign progressed. They lost many thousands of men during five years of campaigns against the Kipchaks, Cumens, Volga Bulgars, Caucasians, Crimeans, and the Rus’; for example, they lost 4,000 men in the spring of 1238 during the single 50-day siege of the northern Rus’ town of Kozel’sk. Of their remaining army, they allocated roughly three tümans to remain in Rus’ to organize and keep an eye on the locals and watch their rear, two tümans for the Polish right flank, and most likely two tümans for the Transylvanian left flank. This left a maximum of eight tümans for the main force directly into Hungary, probably closer to six tümans, and perhaps a lot less. This force may have been increased by forced conscripts from among the Rus’.

The leaders of the central invasion force were:

Batu Khan: 2nd son of Jochi, the eldest son of Temüjin [Genghis Khan]. Both Jochi and Temüjin died in 1227. Batu was about 36 years old in 1241, the supreme leader of the invasion, and the ruler of the Ulus in which this invasion took place.

Subutai: general, spymaster, strategist, tactician and oftentimes commander whom many military historians consider to be the greatest military general of all time. In 1241 he was around 66 years old.

Shayban [Shiban, Siban]: Batu’s younger brother, date of birth unknown.

Bogutaj [Bogutai, Boroldai, Boroldaj, Borolday, Borondaj, Burulday, Burundai, perhaps also Bujgai or Bujakh]: a noyan [general] who seems to be everywhere and nowhere due to the multiplicity of possible spellings of his name, age unknown.

The Cumans in Hungary

The double seal of Queen Mother Erzsébet Kun (Elizabeth the Cuman, 1244-1290), wife of István V (Steven V, King of Hungary 1270-1272). Elizabeth was the daughter of Cuman Khan Köten, murdered in 1241 in Pest.

Source: Wikipedia – Elizabeth the Cuman

As we saw in installment LXIII, in the fall of 1238 some 40,000 Cumans led by Khan Kotian [Köten, Kotjen, Kötöny, Khotyan, Küten, or Kuthen; born 1165] were forced out of the Pontic Steppe east of Kyivan Rus’ lands by the Mongols and fled westward into Hungary. They asked King Béla for asylum in exchange for their loyalty, military support and conversion to Christianity. Some historians claim it was 40,000 men plus their families, but Hungarian historian András Pálóczi-Horváth points out that the land the Cumans were expected to settle on along the Tisa River. could support only 17,000 families. But the nomadic, raiding Cumans did not settle easily among their sedentary neighbors. Robbery and rape by Cumans were reported, then often left unpunished by Béla, who wished no conflicts with Cumans while Mongols threatened invasion. Resentful townspeople began to accuse the Cumans of being agents for the Mongols.

Local autonomies in Hungary late 1200s, including Cumania and Jászság (Eastern Iranian people) in the southern Great Hungarian Plain south and east of Pest. Source: Wikipedia – Kunság

The invitation to the Cumans to become Christians and settle down in Hungary proved detrimental to the Hungarians. When Mongols conquered a people, they considered all those people to be their possession, to do with as they wished. They were, after all, conquered; therefore their lives were no longer their own. The standard Mongol demands of submission included turning over ten percent of conquered people to the Mongols to use as servants, craftsmen, warriors or slaves however they wished. When the Cumans fled the Pontic steppe for Hungary, Batu Khan considered them rebels, escaped chattel. When King Béla gave them asylum and shelter, Batu considered this as justification for his invasion of Hungary, all of which, once conquered, would then become his property, along with all the people, property and land therein. He sent a message to King Béla several times which include the following statement (Historynet-Mongol Invasions):

Word has come to me that you have taken the Cumans, our servants, under your protection. Cease harboring them, or you will make of me an enemy because of them. They, who have no houses and dwell in tents, will find it easy to escape. But you who dwell in houses within towns–how can you escape me?

In February 1241 CE, King Béla IV of Hungary received Batu Khan’s 3rd request for submission, which included the above passage. Béla again refused, but concluded that invasion was now imminent. He sent messengers throughout Hungary carrying a bloody sword — the traditional symbol for a national emergency — calling all ispáns [feudal lords] nobles and vassals to defend the kingdom. They were requested to come to council with Béla at his residence in Óbuda, a small island in the Danube about two miles upstream from Pest. The council went on for weeks. He called too upon the Cumans to whom he had granted asylum in Hungary: it was time for them to return the favor, and they agreed.

Archdeacon Thomas of Split writes in his Historia Salonitana (pg. 257):

At last, roused by their loud protests, the king stirred himself and set off for the furthest bounds of his realm. He came to the mountains that run between Hungary and Ruthenia as far as the borders of Poland. There he went about inspecting all the easiest entry points to breach, and cutting down much woodland, he had long barricades built, blocking with felled trees all the places where transit seemed easiest.

He then sent his palatine [feudal lord of a region] Denis Tomaj [Tomaj nembeli Dénes] into the mountains with a twofold mission: fortify Verecke Pass; learn what he could about the Mongols who had just conquered the Rus’. In early 1241 the Mongols began a campaign of plundering and torching the marches [borderlands] between Hungary and the principality of Halych which had recently submitted to the Mongols; this campaign hampered any attempts at reconnaissance by palatine Denis.

Verecke Pass, 14 Mar 2003. Source: Flickr photo by Ribizlifozelek

The Verecke Pass

Meanwhile Batu and Subutai gathered their troops either at Przemyśl or at Halych — the latter implied by the Hungarian invasion map we’ve been using. Each town was about 120 miles from the pass. Verecke Pass and the mountain approaches to it are not steep: altitude at the north end in Rus’ is 1180 ft (360m), from which the route climbs to 2760ft (840m) then descends to 520ft (160m) over a total distance of roughly 75 miles; roughly an altitude gain of 40 ft. per mile. In late February or early March of 1241 when the snows were still deep, 60,000-80,000 Mongol horse soldiers — plus 1-3 extra horses per man — set out to enter the Carpathians, attack the fortifications at Verecke Pass and descend into Hungary. The map implies that fighting in the pass began on 6 March; six days later they broke through the Hungarian fortifications. Fighting must have been intense to last six days, and with snow, trees, slopes, fortifications and plenty of enemy troops, progress was slow.

1241 Central Europe invasion, movement, and exit routes; Josef Szabo.

Source: Academia – Mongol Invasion of 1241

In his Historia Salonitana, Archdeacon Thomas of Split had this to say (pgs. 259-261):

The period of Lent went by, and it was close to Easter [on 31 March 1241, Julian calendar] when the entire host of the Tatar army burst upon the realm of Hungary. They had forty thousand men with axes who went in advance of the main host cutting down forests, laying roads, and removing all from the places of entry. They were thus able to surmount the barricades that the king had had prepared as easily as if they were made of chaff rather than of great fir trees and oaks piled high. It took little time to trample and burn them down, and they offered no barrier at all to their passage. When they came upon the first peasants in the country, they did not show at first their full savagery of their ruthless nature, but simply rode through the villages and seized plunder without doing great physical harm to the populace.

From The Mongol Invasion of 1241, János B. Szabó (pg. 81):

It was here that a messenger sent from the border by Palatine Denis of Tomaj arrived with the news that the Mongols had reached the Russian Gate (the Verecke Pass) and demolished the defensive works. The Palatine’s army was unable to stop them, and even Denis himself was barely able to make it back to the king, accompanied by only a handful of his soldiers.

Seal of Denis (II) Tomaj (1237), Palatine of Hungary 1235-1241.

Source: Wikipedia – Denis Tomaj

Denis, severely wounded, escaped with a few men and raced as best he could to Béla — still in council in Óbuda — to report the defeat. The Mongols were now in Hungary and for all Denis knew, not far behind him. Denis then went the few miles downriver to Pest to recover from his wounds and continue in service with the army.

Óbuda is the closer island in the Danube; in the distance Buda (R) Pest (L).

Source: XPatLoop – Óbuda Island

Entire Mongol Empire & Rus’ Series: Click Here

First Installment: Why didn’t the Mongols Conquer Europe in the 13th Century?

Previous Installment: Mongols in the Great Hungarian Plain || Mongol Empire LXXXVIII

Next Installment: Tatars in Pest || Mongol Empire XC

This Installment: The Verecke Pass || Mongol Empire LXXXIX

Sources

History of the Bishops of Salona and Split (Historia Salonitana);Archdeacon Thomas of Split, General Editors: János M. Bak, Urszula Borkowska, Giles Constable, Gerhard Jaritz, Gábor Klaniczay; Central European University Press, 2006 Budapest and New York. Link to free PDF.

Mongol Invasion of 1241 and Pest in Hungary, The; János B. Szabó; Academia.com. Link to free PDF.

HistoryNet – Mongol Invasions, Battle of Liegnitz

HistoryNet – Mongols on the march & logistics of grass

Historum – Military History – Mongol siege fighting on foot

Quora – How did Bela IV retake his country

Wikipedia – Batu Khan

Wikipedia – Boroldai

Wikipedia – Carmen Miserabile

Wikipedia – Carpathian Mountains

Wikipedia – Central Europe, Mongol Invasion of

Wikipedia – Denis Tomaj

Wikipedia – Holy Roman Empire, Mongol Incursions into

Wikipedia – Hungary, First Mongol Invasion of

Wikipedia – Mohi [Sajó River], Battle of

Wikipedia – Mongol Invasions and Conquests

Wikipedia – Rogerius, Master

Wikipedia – Subutai

Wikipedia – Veretskyi [Verecke] Pass

You must be logged in to post a comment.